|

Ekphrasis magazine was thrilled to sit down with Emily Robinson, writer, director, actor, producer – and Ekphrasis alum. Our discussion, centered around the release of Emily's debut novel, Consumed, touched on everything from daily writing habits to Italian vineyards, to the queerness of body horror as a genre. We invite you to discover Emily's work by picking up a copy of Consumed from Grey Borders.

This is your debut novel, but you’ve been a writer for a long time. How do you feel like your writing has changed over the years, and how would you describe your writing practice? Emily Robinson: My writing practice began as a reading practice, or really, an addiction. I loved books and I idolized the people who dreamt them up. My earliest writing began as a ritual, or a routine attempt to become someone who created the magical thing that I loved: books. I wrote badly and I wrote constantly. Diary entries exclusively about crushes and the secret languages my friends and I schemed up…. In retrospect, it’s strange to say that in high school I first began sharing my writing more publicly. I started writing articles here and there for online publications and developed a short film. I had this raging desire to connect and create, to take the private practice of putting words on the page and bring it into a space I could no longer control: the wider world. Some people have a rigid writing routine: two hours everyday or 1,000 words, no questions asked. I wish I kept such a schedule. Sometimes I manage to for a number of weeks or months, but rarely longer than that. When I’m writing for myself—not for a contract or assignment—I write when I have something to say. When it’s hard to focus, I treat myself to fancy coffee shops to force myself to sit down and get down whatever’s coming up. It comes in waves. Some days, I could write for hours and hours and barely come up for water. Other days, I have to push myself through the hurdle or dive deeper into the blockage. Why am I stuck?? As I’ve begun to write more and more for work, I’ve found it trying at times to retain the creative spark. I’m a fiend for more experimental writing exercises. I love to be pushed outside of my mind, forced to create something within parameters. Sometimes I gift myself writing assignments to push my craft and my brain forward. The results of these writing experiments are private and are not meant to be shared. While writing is about communication, it is also personal. Sometimes the only person with whom you need to communicate is yourself. I try to allow myself that gift when I need inspiration. In short, it ebbs and flows. Every time I write, it feels new again. In Consumed, your protagonist Amber escapes the sweltering heat of a New York City summer for the vineyards of Italy – a trip you yourself have made. How was this novel born of or borne by your travels? Did you find Amber and Natalia, or did they find you? ER: I have always found that I write what I need to read. In high school, I wrote a short film about a girl losing her virginity and questioning her sexuality before I was able to do either myself. Consumed is a much more esoteric approach to this same idea. When the story was conceived, I was dealing with an incredible amount of inner turmoil, and unable to look previous violations of my body in the face. I went to Italy and had barely any access to WiFi, finished the books I brought too quickly, and found myself bored, with nothing to do but think. Thank god I had my computer. I began to write. The structure came quickly. The approach, not as fast. Over the next year or two, I developed the novel in my writing classes at Columbia. I was very fortunate to have generous readers and professors who helped me push the story in the ways it needed to be pushed. I am not a fan of horror for the sake of horror. I really tried my best to avoid writing some of the more gruesome scenes. Through workshopping, it became clear that I needed to go there in order for the story to work. I’m so glad I did, even if there were a few nightmares along the way. Your prose is contemplative, deeply atmospheric, and imbued with a creeping, uneasy sense of dread. How did you go about finding and honing this voice? What inspired the gorgeous viscerality of this novel? ER: The writing process began during the summer after my sophomore year of college. My mind was swirling, overcome with texts on morality, love, desire, overwhelmed by experience, heartbreak, violation and violation and violation. The cadence came from muttering the words aloud as I typed. While the book is written in the third person, it is an extremely close third person. It is an inner monologue. An inner monologue gone wrong. The lyricism emerged organically and felt integral to the story. The reader needs to be lulled into the crumbling world that is Amber’s mind. Let’s talk cannibalism and queerness. What inspired those delicious eating scenes? And do you see these themes as interrelated in this novel? ER: Though cannibalism in literature is by no means a new phenomenon, it is certainly having a moment. To me, it was inevitable that it would become the climax of this book. Consumed, as the name suggests, is about consumption – of content, of food, of people. It deals with incredibly dark themes, and, ironically, the cannibalism is not the darkest. The cannibalism is done out of love, out of preservation. It is the life raft, an attempt to save a person dying from the abuse that is common in our real world. I find it hard to write about without spoiling the novel, but all the relationships in the book are difficult and imperfect. The book is a grasp at healing. Amber flees New York to escape trauma, to move on and forget – but her body is smart, and it will not let her. She is on the verge of collapse when she falls in love. And it is through that love, even if it lacks healthy boundaries, that Amber glimpses her own freedom, even if it’s not enough to save her. That’s the tragedy of the novel. There is love and there is healing, but it is not enough. She needed to save herself, and she couldn’t. It was too much. The queerness of the book exists in the way it does, because it made sense within the context of Amber’s world. That’s likely because, surreal elements aside, the world in which Amber lives is very similar to my own. I’ve lived in New York, traveled to Italy, worked on a vineyard, and I’m queer. The people and places and ideas that I have are certainly informed by that. Stories of healing—whether they end successfully for the protagonist or not—are complicated. It’s hard to write the intricacies of what feels safe and what doesn’t. All I know is there was never a world in which Amber would fall for Luca. Her great love had to be Natalia. Body horror is a heavily cinematic genre, and your background in film clearly informs your prose. Can you talk a bit about your influences, from film, TV, literature, or elsewhere, and how you write with such a clear voice while also paying homage to other artists? ER: There are so many influences. For starters, I’ve never written a book that has talked directly about so many artists and inspiration sources. However, Amber is in college, at a point in her life where everything feels new and big and vital. Her perspective is still emerging, and it feels like a discovery bursting from her body. Once she sees the art of Lucio Fontana and Caravaggio, she sees it everywhere. It was freeing getting to dive deep into her obsessions and inspiration. In my opinion, everything is in conversation with everything else, even if you, as the writer, are not aware of the conversation. To make it distinct, you have to have something to say. You have to have a perspective of your own. In no particular order, some references: Movies: Der Fan, Possession, Swallow, Raw, The Stendhal Syndrome, Spencer, Call Me By Your Name, Crimes of the Future, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Sick of Myself, etc.. Writers: Carmen Maria Machado, Melissa Broder, William S. Burroughs, Larry Mitchell, Hilary Leichter, Andrea Lawlor, etc.. Musicians: 100 Gecs, Max Richter, Anna Meredith, Dustin O’Halloran, Kim Petras, Soléy, SOPHIE, Angel Olsen, Rina Sawayama, Kate Bush, Johnny Greenwood, etc.. Consuming takes many forms in this book. What are you consumed by now? ER: I’m consumed with so many things! Good coffee, Breath of the Wild, arts and crafts, adult friendships, my exercise box (yes, I’ve written about her for Ekphrasis!), being in love, morning walks, the return of the romcom.

1 Comment

by Mischelle Anthony Photo credit: New York Public Library Digital Collections It’s clever, this photograph of a processed

photograph rendered too late, an abstract cloud of dust. O tornado caught in time, O funnel cloud of barn planks and grime, your boundaries symmetrical, liquid, smooth as the red wine glass that we never put in the dishwasher. That I did, though, last evening: force the bulb against the pale not-quite-sky blue, thrill at the *thunk* as rubber spikes hover above the washer door and its viscous finger-y drips, factory special white as photo paper, white as the noise, the buzz of the vintage radio behind every song and newscast we choose to hear instead of each other. by Daniel Sofaer Photo credit: National Museums NI The sky above him has eyes of its own.

The light that gathers in the pool is on the watcher’s mind because he is wearing turquoise blue. If he hadn’t turquoise blue, the mountains behind would not be pink, and his blue mind would not have known how to sink into that luminous pool, snaking towards us at the very edge of time. Watcher, crouched you, blank-faced \except the barely glimpsed eye, why do you wear blue? I am a berry, juice of the sky. Watcher, what say you of the blue? Go when ready. I will follow you. Follow me? I wear no green, agreed-upon garb of the peasantry. O AE, only a poet could have painted this badly. If he’d known how to paint too well the watcher could not have sat at his well. Oh bother the great paintings anyhow! Darkness rests on purple field. On purple field the darkness rests. Watcher, who the hell are you? My sky is tawny with exploding cloud. He cannot see the source of light; we think we do. The watcher cannot see the source of light, only its reflection in the pool. We can, if we choose, embrace the sky, or watch the watcher, watching at his pool. by David Blumenfeld Image courtesy of David Blumenfeld He looked so old, with his deeply wrinkled face, watery eyes, bushy white beard and few sprigs of silver hair protruding from his yarmulke. My paternal great-grandfather’s photograph, framed in elegant black with gold trim, hung in our house for as long as I can remember, probably from before my birth in 1937. According to family lore, he lived to have a second bar mitzvah, which, my aunt said, took place in nineteenth-century Romania when a congregant reached 113. Family myth, I thought. People didn’t have accurate records in those little shtetls. Who knew for sure their true birthdate? Any very old man (alas, no women) might have been honored with a second bar mitzvah. Yet I wanted to believe that despite the poverty and destitution, the pogroms, and endless other hazards in those beleaguered ghettos, one old Jew in my family line somehow made it to 113. I still want to believe it. Recently, I learned that --- based on Hebrew Bible 90:10, which says a normal lifespan is 70 years --- those who celebrate a second bar mitzvah actually do so at age 83. Maybe in old Romania, they celebrated it at 113. Or, maybe the custom was 83 even back then, but my great-grandfather lived to 113 anyway. I’ll never know for sure how long he lived but I’ll die hoping he made it to 113 and had a second bar mitzvah. In the meantime, I’m overdue for my second bar mitzvah: I just turned 85.

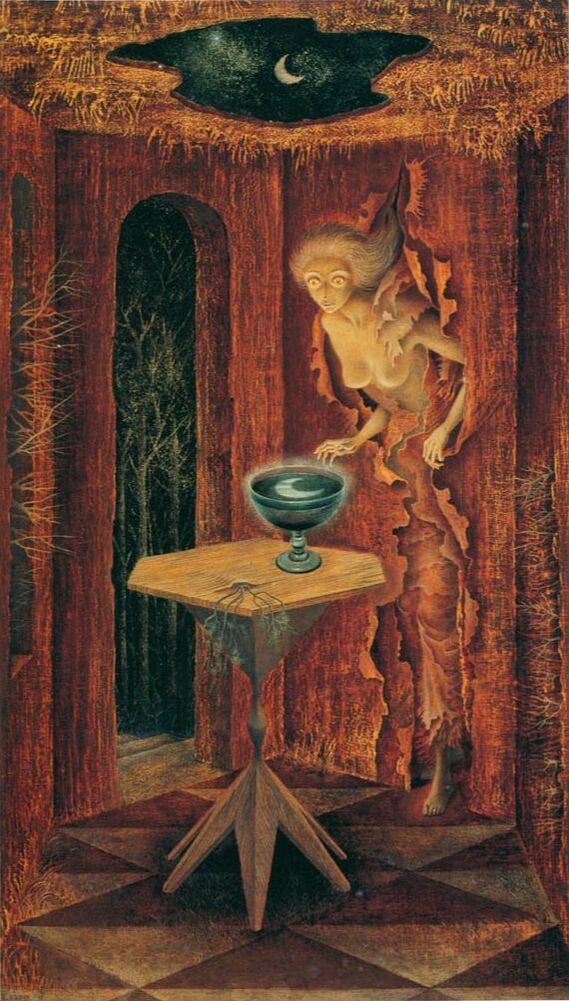

David Blumenfeld (aka Dean Flowerfield) is a former philosophy professor and associate dean who in retirement returned to writing stories, poetry, and children’s literature, which he abandoned in his thirties to devote full-time to philosophy. His recent publications appear or are forthcoming in The Caterpillar; Best New True Crime Stories: Well-Mannered Crooks, Rogues & Criminals; Mono.; Beyond Words; Balloons Lit. Journal; the other side of hope; Sport Literate; Better Than Starbucks; Smarty Pants; Drunk Monkeys; The 3rd Act; McQueen’s Quinterly; Holyflea!; The Parliament; Bloom; The Dirigible Balloon; Moss Piglet Zine; The Bluebird Word, Lighten Up Online, and various anthologies. by Christien Gholson She pushes through matted roots, emerges into an earthen room,

sees the root-sprouted table that holds a water-filled grail. She emerges, lit from within, from the sun inside the earth. Call her Luminar. In the middle of a busy bookstore, I recognized that image though I’d never seen it before. How did she know what had been inside me since birth? A hole in the root-ceiling revealed a crescent moon, reflected off the water’s surface. She stares into the reflection, entranced, pleased, at the threshold of the room she has been searching for her entire life, but hadn’t known existed until that moment. Call her Liminar. And I stood there, looking down at that painting, Luminar as Liminar, entranced, perpetually breaking through, into the secret, rooted to a room moving in and out of time. I was the chalice bearing the moon’s illusive tracks; the woman hatched into the root-room, discoverer and discovered at the same time; the slim arched door beyond the table holding the grail, opening out to distant bare trees, night trees, keeping silent vigil. So many selves suddenly available. Now, every time I look at this painting, she says to me: We are not just one thing, never just one thing. I take in a deep breath, my first breath… Christien Gholson's "Jésus-Christ nous offrant son sang" and "Inside Leonora Carrington's Painting the Giantess While Standing at the Edge of a Pond" also appear in Volume IV of Ekphrasis Magazine. by Ethan Fenlon Artist’s statement: This project began as a digital collage of five photographs. To doctor the image further, I used DALL-E as an artificially intelligent editor, blending the edges of each frame together and mixing perspectives. The ten captions below served as the natural language prompts I fed the computer to achieve the final result.

by Diana Gordon After Cloud Nebulae, oil on canvas by Claudia Sperry Fingerprints smeared through rivers of raw umber, like tedders through a hayfield. Humid.

I see, like turtles and dogs in clouds—smog from a distant metropolis sweating on sweet grass. A clawed canvas, marks wanting in, paint under nails wanting into the divets of rough weave, wanting something not yet visible, guarded by a family of ghosts. Huddled. I see rust under an August sun. Hay shining far from the sea. The ghosts squeezing out of hedgerows, aching for what ghosts ache for. In the real world, a grasshopper creeps on a wicker tabletop. Each leg deliberate, the hindmost raspberry red, backlit by sun. A canopy of oak leaves. Undulate. The insect can’t perceive the reality of me, too huge, too near, nor my kiln-fired mug as it tiptoes by, its great eyes useless if I were the sort to squash grasshoppers. This is all. Oil paint, mineral tint, a field. Rust, hay, sea, longing. Clouds. One grasshopper, petticoat wings tucked, walking on wicker. by Ryan Harper "City of Night" by Courtney Eileen Fulcher I.

The city emptied beneath argument: manhole flush, respiration of the lasttrain, left and clean with leaving—brick and mortal. All madnesses enlarge, all gone remote: no street on which to throw the paper, no tracts wagging in jambs— clean in left light— finished of men— slouching in delivery, one man, his heavy foot scooting down the stairs, collides with the white day—staggering— squints to clear orders, bare plans. One man hides high in the cupola—dodging clappers, the furious tweets of the nervy passerine— muted mass through the cathedral doors, turgid as a blurred breviary— liturgies of the blunt headland—these are columns that were our legs— walking latent through the drowsy little hours— behind the doors assume scriptorium: guess on the senses, pray the nones finish the afternoon fleshed to evening. II. Not looking himself, not seeing others looking, the architect knocks across his plaza, steps out the central glare into the gray academies, to the shadows of the arches where the heat arrives in teams. In high contrast the essential hands the keys the crown of the metropolis; most deaf, the sleek colossus surgical in his site— fluting soft, cella by far light— secures the balustrades against everything on this earth. Stupefied with white dreams, the architect accepts flecks of necessary motions, in remainder: if need be, the vapor trail, departing mow of helicopters; if need be, the blue gull, faint bossas of an afternoon—allowing for the roulade hummed brief in the corner, or loudspeaker summoning brief, bull- throated, a bid just out of frame, completely out—enough of men in the fatigue of little hours. High beneath the rooftop water tower, in strict and sliding shade, a woman paints over painted figures she has visited— downstairs descending, the grid becomes prismatic, the splintering thesis of a lost errand. The omnibus topples open; now she is off, en route, retrieving, letting be the riders slumped in portrait, breathing slow before the passing rooftops—frieze, dormer. III. Alternating clouds—rose before the flower shop, trash of weekend, sweet challah, damp jubilee of the street sweeper, doormen watering the tree pits— premier the tender ratchet up the gates—bodega dominoes tumbling open, shopworn by first browse the holders having groped through stocks, the absent subject. The palazzos, bald in distant light, retain symphonic themes on condition of the minted corners—city zoned in balking strains for cloister, carnival. These naked, bashful publics— clanging pots on the rooftops, hustling down the esplanade, murmuring stern refrains, delivering the remote order—squint for the grandeur of clean space—respire, fantasizing flesh enmarbled— leave the square its grand and strangled hours— pretending all exercise an option— pray the nones—the amen corners, ruins, the city ideal. Ryan Harper is a Visiting Assistant Professor in Colby College’s Department of Religious Studies. He is the author of My Beloved Had a Vineyard, winner of the 2017 Prize Americana in poetry (Poetry Press of Press Americana, 2018). Some of his recent poems and essays have appeared in Kithe, Consequence, Fatal Flaw, Tahoma Literary Review, Cimarron Review, Chattahoochee Review, and elsewhere. A resident of New York City and Waterville, Maine, Ryan is the creative arts editor of American Religion Journal. by D. Walsh Gilbert — after Crab on Its Back, Vincent van Gogh, (Netherlands) 1889 and in conversation with “Canticle in the Fish’s Belly”, Hundred-Year Wave, Rachel Richardson

Netting and an ostrich-feather headpiece pinned to auburn chignon braids gathered and lifted off freckled shoulders, off vintage silk and lace, while breaking offshore, knee-high waves collapse tenderly at low tide. No one notices the crab. The sun. The sand. A walnut cello. And a gull among the guests. At the end of the vows, while time eloped, a stroll down Folly Beach, South Carolina, barefoot until pictures snapped catch what’s missed by anyone not present. ‘This, shipmates, is that other lesson’: the green copper blood in a single-chambered heart of a back-tipped crab Once turned onto its back, belly-soft, pinchers catch sea mist-- parched and praying for the moon to do its job. The gull notices. We know down deep, sea crabs can’t feel raindrops pummeling the ocean. Storms rift overhead, but at the water’s edge, veiled in seaweed, upended and overset, everything is different. D. Walsh Gilbert's piece "Fish in the Middle of It" also appears in Volume III of Ekphrasis Magazine. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed